Let’s talk a little bit about sidekicks in video games.

Up until now I’ve been doing a lot of talking over the similarities between science fiction in games and literature and film. But on the point of sidekicks there is a yawning gap, and it is one of the few places where the requirements of the medium is the key driver.

In literature, we develop a connection to the hero through their interactions with other people. How they behave with both “good†people and “bad†people tells us who they are and why we should be rooting for them. The sidekick often serves as a key element of this. The sidekick is often the one person who sees the “real†hero. They be the vehicle by which new and unfamiliar elements of the world get explained to the player/reader. They are the place in the story where theories can be surfaced and narrative plot points exposed. They help contain exposition and ensure that the player/reader knows exactly what they need to, when they need to.

The more far-future and fantastic the world becomes, the more essential this kind of character is. They serve multiple roles, all of which help to drive player/reader engagement.

Video games have a long history of “waste not, want notâ€. Every asset is created by a team of people, and as such holds a lot of value. If a pixel is on your screen, then it has a purpose. There’s a reason for it to be there. This goes doubly so for a character. In games, the sidekick usually serves a number of functions. They are there to impart world information that the player might not know, they can carry your swag, they can fight alongside you, they can provide clues and useful information and can keep you following the right path towards the final Boss.

But, in games, the sidekick is not really the medium via which the player/reader gets attached to the hero. In games, the player *is* the hero. Players map themselves, unconsciously or consciously, onto the main character of a game. We don’t have to establish a connection because we *are* the connection. Whether the games point of view is first or third person, whether it’s a strategy game or a puzzle game or a simulation, WE, the person/s playing the game, is always the hero.

So the value of the sidekick in terms of the narrative changes. And, to be honest, it gets a little weird sometimes.

Humans attach themselves to things. Pets, cars, plots of land, other humans. It’s is one of our defining characteristics; that we seek a connection and almost any interaction is improved by the existence of said connection. This includes the arguably solitary experience of playing a videogame. Players in games get unreasonably attached to their sidekicks. Whereas, in literature, the reader is expected to empathise with the main character when their sidekick gets kidnapped, or broken, or killed, that relationship is still one step removed. In games, that relationship is *personal*. The player is not observing from even the comfortable distance of the written word. This is fan-fiction levels of personal.

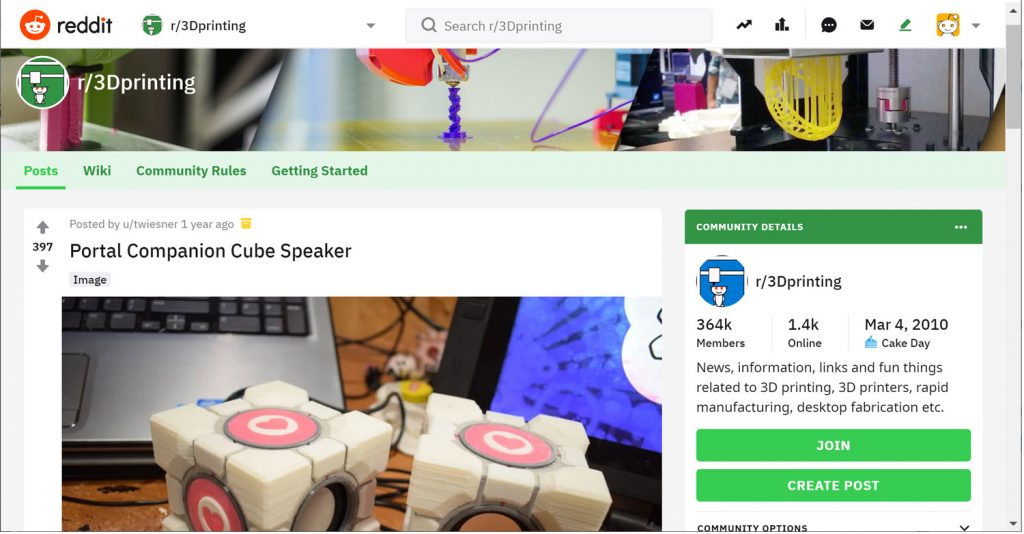

As an example, the Weighted Companion Cube in the game Portal starts out as a bit of an inconvenience. You need to carry it around and use it to hold doors open, solve puzzles and an array of small tasks. All the while, the research AI keeps talking to you as if the companion cube is an actual living, feeling companion. You are warned that it will never abandon you, that ideally it will never stab you or cause you bodily harm in any way.

There is never any indication that the cube is anything other than an extra-fancy box with hearts painted on it. Players drag it around, use it to advance through the level, giggle at the research AI trying to convince you that the cube is alive and has feelings.

And then the player must destroy the cube in order to advance to the next level.

This moment in the history of game-playing has become near-legendary. This is the moment that the Weighted Companion Cube goes from being an inanimate object, to something that players are willing to fight and die for. Thousands of hours have been spent trying to find a way through this level *without* the need to sacrifice the Companion Cube.

This inanimate cube has spawned poetry, fan-art, postcards, mini-films and even wholly cube-centric game experiences, and this “sidekick†is by no means alone.

In linear narratives (film and literature, primarily) once the sidekick has served their primary purpose, once they have brought the reader into the world, shown them how to love the hero and read them in on everything they need to know, they become a primary plot-driver as often as not. They get killed or kidnapped, held hostage to ensure the hero’s compliance (which never works), sometimes they turn evil.

But in video games it’s almost an unwritten rule that the sidekick cannot be used as a direct plot driver. Which seems a little odd, given the strong responses shown above to Lydia and the Companion Cube. They can retire, they can get married or simply quietly vanish, written out of the story or converted to an average NPC after the last training quest, but the minute you try to take overt *advantage* of a player’s ability to get attached to the sidekick, something strange happens.

The player stops caring.

And this happens for a very simple reason.

The goal of a game is to play the game. This high-level understanding is present all the time in most players (there are, of course, always exceptions). The moment you impinge on this suspension of disbelief, the moment you try to coerce a player into an action through emotional means, the game ceases to be player versus game. The game becomes “player versus game designerâ€. Players stop playing the game as it is laid out before them, and they start playing the higher-order “meta†game.

Meta gameplay is different from immersive gameplay. In immersive gameplay, the player is functioning as a part of the in-game world. They are in tune with the game’s mechanics, with the quirky physics, the occasional visual glitches. They are *forgiving* because all of these things are part of that world, flawed though it may be. The rules of that world are established and they will accept that cats can be blue and if you just hit the controller buttons fast enough you can fly. The same way the reader of a novel will accept that FTL (Faster than Light) travel is the kind of thing a two-seater life-pod can easily handle.

But once a player starts playing the meta-game, they cease to be immersed. Once the emotional blackmail kicks in, they will take a step back and evaluate everything more rationally. They will break their emotional connection to the sidekick because suddenly that sidekick has become an object. They have become a piece of the game mechanics and as such the player knows they are now disposable in the service of the game’s designer. And in order to complete the game, the player will need to be ready to sacrifice that sidekick.

It is a key point of difference between the use of the sidekick in games and the use of the sidekick in more linear storytelling, like games and film. And at the end of it all, the reader can breathe a sigh of relief that Han and Chewbacca are back together again, but the game-player must mourn the loss of the Weighted Companion Cube, even if they’ve found a way to beat the level so they survive.