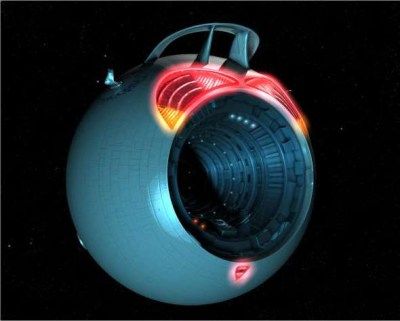

Other than Aliens, is there anything more science-fictional than spaceships? I think not. From the earliest days of cinema we’ve had a fascination with the kinds of vehicles that get us off the planet we were born on and out into the vastness of space.

So let’s have a little conversation this week about a particular kind of vehicle. Your hero or main cast-member’s one true love. Their one and only reliable family member, the one thing they will fight and die for before the narrative turns them into somebody with a wider gaze.

You know the ships I’m talking about, the Millennium Falcon, Serenity, the Tardis, the Heart of Gold… (just to name a few of the best known examples). The idea of vehicle as compatriot comes through into many other genres, it’s not restricted to science fiction. Travis McGee’s Busted Flush, Eleanor from Gone in 60 Seconds, Betty from American Gods are just a few of these reliable yet non-conversational characters.

It is interesting, isn’t it, that undying love and loyalty often appear in the guise of a machine.

Now in keeping with my usual game-centric theme, I’ll point out that video games don’t tackle these kinds of relationships unless they are working with somebody else’s intellectual property. We don’t tend to build them into our own narratives. There are a couple reasons for this. The partnership of person and machine seems to be outside the usual run of video game protagonists and sidekicks.

Wait, wait, wait… I can hear the laundry list of objections rise to your keyboard and those will be addressed shortly.

To the difficulty in bringing a vehicle to life games is less of an issue with making an inanimate object come to life and more in a question of game design.

So let me ask you, when was the last time you played a game that took place in a single room? Or even a single level? Yes, there are exceptions, especially in the indie game arena, but having the game design a character locked into a single place becomes a challenge. A place that the player has to return to in order to gain a narrative interaction becomes a weight. It becomes the kind of thing that slows a game down. The player may have progressed through the tasks or other requirements, but the psychological heft of that space and their need to return to it can cause a game to feel restricted, held back.

This is a very different effect than having a home-base, like the Tower in Destiny. A companion-vehicle is a character in their own right rather than simply a location. And as a character they are most effective via their interactions with the player. Their very nature prevents them from having any other expressive outlet.

In order fulfill their role as a character they have to be able to travel with the player, otherwise all your gameplay happens in isolation.

All of this means that these kinds of characters have been eliminated from games almost entirely. Instead of the “ship with a soul†video games lean into the “Swiss Army knife sidekick†idea. Our loyal and sometimes less than on the ball machines are no longer vehicles, they instead travel with the player in a much more literal sense. They posses a physical form like the Ghosts in Destiny or they are mobile through the use of communications equipment. In almost all cases they lose the communications barrier that is often used to great effect in film or television. They stop being the unusual, slightly magical vehicle with a soul and instead become a full-blown member of the ensemble cast.

Which brings me to point number two. Communication, or the difficulty thereof.

The trick with nonverbal communication, like the Doctor ranting at something the Tardis has “said†or Han sweet-talking the Millenium Falcon, is that it’s remarkably hard to do in games.

We don’t know if the player on the other end is going to be an extrovert or an introvert. Are they going to be the kind of gonzo player that likes to pull a full-blown “Leroy Jenkins†and go charging into the battle at the drop of a hat? Are they going to be interested in the more subtle world-building elements or are they only going to be interested in which problem to solve next? In order to make an interaction work between player and vehicle work, the nonverbal communication of the machine has to be recognized and understood by the player.

In cinema/television and even the written word, this is a far easier thing to accomplish. Your main character and your sidekicks are matched, even designed, to work well with one another. The doctor never misunderstands the Tardis unless the narrative requires him to do so. Han and the Falcon always seem to know exactly what to say to each other at exactly the right moment.

But in video games we have the randomness of an unscripted interaction. You might have a player who decides they’re not going to put up with this ship’s bullshit and will ignore every type of communication other than the written word. You may have another player who is so into the interaction between themselves and the ship that they fail to execute the rest of the game in any meaningful fashion.

These are both perfectly valid styles of gameplay, but the disconnect between them and the larger game experience becomes a problem in a world where you want a player to feel rewarded and fulfilled by the end of the experience. Both of these play-styles really need their own style of design and the vehicle-as-family is not a robust element on it’s own to base an entire game around.

Add to that the fact that one of the key problems with allowing for miscommunication in video games is that the game player is never sure if it was done on purpose. Was it included for a narrative reason? Did they miss something? Is it a BUG!?! The uncertainty factor is high and can make disruption of the overall gameplay experience a very real possibility if the developers don’t take the proper care.

As a closing example of mysterious communication, I will point you at the Myst games from the 1990s. Created by the developer Cyan, Myst and it successor Riven, were some of the original blockbuster puzzle games. It’s the mystery game by which many science-fiction mystery properties have been held to as a standard and it serves as both an example and as a warning.

More players rage quit this game because they were unable to find a clue then any other game at the time. It was hard, intellectually hard, to get through from start to finish. It required taking, maps, careful thought and even a bit of library research in order to complete. Millions of people played and millions of people failed to gene get pat the first level of the game.

BUT. In order to tolerate that level of frustration on the part of the players, you have to have millions of game sales. It’s not enough to be hard to play, there has to be a compelling reason for players to put up with the effort and trouble. It’s not the kind of thing that you want to be banking a multi-million dollar investment on.

So if you’re looking for that silent sidekick. That quirky vehicle that manages to make sure you end up in the right place at the right time in order to continue the story, video games are probably not going to give you that kind of interaction. At the moment that is still comfortably the purview of film television in the literature, rather than video games.

But give us time, we’re going to figure it out.