You knew we were going to get here sooner or later, didn’t you. One of the most interesting things about aliens showing up in videogames is that they often serve the same purpose as they do in broader science fiction.

So let’s talk about aliens in videogames a little bit. You knew we were going to get here sooner or later, let’s be honest. When you say “science fiction“ to your average person, rocket ships and aliens are the two things that come to mind first.

Rocket ships we will tackle another day.

Video games love their aliens. When games first started out, decades ago, there was a resistance to having human-form enemies. Mowing down ranks upon ranks of little pixelated people was simply not the way things were done. Never mind the fact that the state of graphics at the time gave you “people†that were on a par with your two year old’s first chicken scratch attempt to write his or her name.

In response to this, having your game take out hordes of aliens, or zombies, or skeletons was an easy way to get humanoid looking enemies while not crossing that invisible line that denoted people as bad-guys was one step too far for light entertainment.

And as an industry we have used aliens heavily ever since. Not always in science fiction stories (okay, granted, some might argue that the mere presence of an alien from outer space categorically defines a work as science-fiction, but I would argue that you’d need to look at the use-case… *cough cough GTA*). Sometimes it’s a tongue-in-cheek presentation, sometimes there’s a key element of plot that revolves around an alien presence, sometimes they’re just there as enemies, as friends and all the grey* spaces in-between.

Faceless opponents:

Faceless hordes are the oldest trick in the book where videogame aliens are concerned. Earliest games like Galaga and, of course, Space Invaders just threw hundreds of copies of the exact same sprite (or pre-programmed set of pixels) at you over and over. Sometimes in waves, sometimes in small strike forces and every so often you got to fight a big, bad boss. Because the levels were often “procedurally generated†(ie, created by the software following a set of rules, rather than designed by hand) these games could literally go on forever, if you had enough quarters in your pocket.

These types of “wave tactic†aliens show up in literary science-fiction as well. Novels like “Starship Troopers†boast aliens who rely on the kinds of military tactics that involve throwing hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of bodies at an opponent, overwhelming them by sheer numbers rather than brinkmanship. While literature has the time and pacing to go deeper into the motivations of these kinds of aliens, in “wave†games the focus is usually tightly tied to the gameplay mechanics and the motivations are left to the imagination of the player.

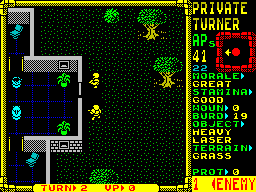

While many of the early 8-bit games relied on this kind of wave attack to extend gameplay time (and to keep you feeding quarters into the machine), more recently they have evolved into RTS (Real Time Strategy) experiences. The pace is a little slower, but the enemies keep coming and, beyond the basic “invasion” premise, the specifics of why they are invading and who they are tend to stay very sketchy in-game. They are invading, you’re defending, get down to business.

They’re not all bad:

The alien with the heart of gold is a popular idea, not least of all because game players love the idea of a redeemable villain. Sometimes the alien is the protagonist (as played by the gamer), sometimes a sidekick or sometimes a helpful NPC (non-player character).

Most of the time when we find the “not all aliens” idea popping up in games, we have a clear point of reference between the “good guy” alien helping us out and the cast of characters arrayed against the hero. (This, by the way, is a different scenario than a traitor “mechanic” which is rare in videogames, but pops up a lot in traditional tabletop games). In order to make this effective, the presence of the “good guy” alien is often revealed later in the game and the player is often privy to the events that cause this change in the alien’s mindset.

In Halo 2, for example, we are introduced to the Arbiter, a disgraced Elite warrior of the Covenant who is offered a chance to redeem himself by taking on the mantle of Arbiter (a position nobody holds for long). The game then splits the player’s gameplay time between the Master Chief and the Arbiter as both storylines head towards a collision. By the time they meet in-game, the Arbiter has achieved a greater understanding of just how his people are being manipulated and the Master Chief has come to understand that the Covenant are not just a monolith. There may be a way to bring some of the Covenant factions over to humanity’s side of the fight.

They are way cooler than us:

The deeper we get into the backstory of any aliens involved in a videogame, the more narrative elements the game is going to have. On the simplest end, we have our “invading aliens” shooters like Space invaders, but at the complete other end of the spectrum we have large, complex action RPG’s like the Mass Effect series of games.

Not only does the braided narrative of Mass Effect allow the main character to develop along the lines of a player’s personal preferences, but it incorporates multiple smaller storylines as well as an extensive Codex or world and background information on pretty much everything in the world a player might need to or want to know. This level of depth allows the game to deliver multiple elements on the theme (Forerunners, as an example) that would normally be more effectively done in a literary form.

Much like different races (Orcs, elves, etc) in Fantasy RPG’s, aliens in these larger-scale properties tend to be better than humans along a particular axis. Stronger, faster, better able to use certain technology, psychic, whatever the improvable characteristics are, you will find them sorted between the different alien groups with humans as the “base standard”.

Comedic intent:

Funny science fiction is a subset of the genre that comes and goes depending on the talent that’s available to write it. Some years we have works of literary genius, some years everything seems to fall flat. Comedic intent can be anything from wry tongue-in-cheek references to popular culture and alien bobbleheads popping up in your hot-rod’s glove compartment to full-on situational comedies involving romance, mistaken identities and good old-fashioned fart-jokes (because every culture, on every planet, has a place in its heart for fart jokes).

There is an inherent ludicrousness in the presence of aliens in standard urban environments and scenarios. In the much beloved “Surgeon Simulator” we find a game that already borders on the silly, due to the sub-par physics-based nature of the controls, taking it one step further by handing the player an alien autopsy to take command of. Sometimes they are a perfectly serious inclusion in an X-Files type scenario, sometimes they are an out-of-the-box type situation (a-la Valente’s Space Opera) where the entire narrative, from the aliens to the circumstances is so far outside the norm that everyone involved just accepts the wackiness and moves on with their lives.

*speaking of humor, you didn’t think I could avoid working at least one pun in here somewhere, did you?

Wrap Up:

In videogames, aliens are one of the most versatile elements you can work with. From providing much-needed comedic relief to setting the basis for a well-balanced race and class system, adding aliens can mean adding critical gameplay elements and narrative backstory that will improve a wide variety of game styles and genres.